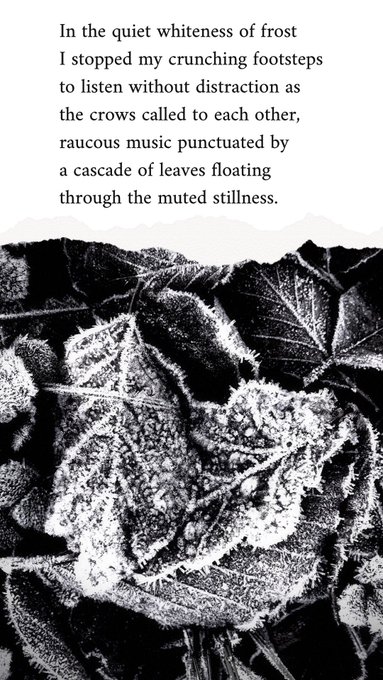

What birds fly with you,

ibis or swallow,

we do not know

nor how light the feather

to weigh against your heart

Last lines from

‘Elegy for the Mummy of a Young Girl

in the British Museum’ by Frances Horovitz

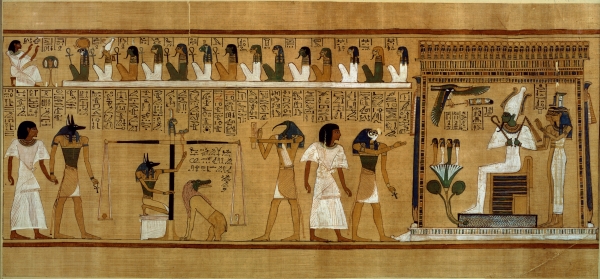

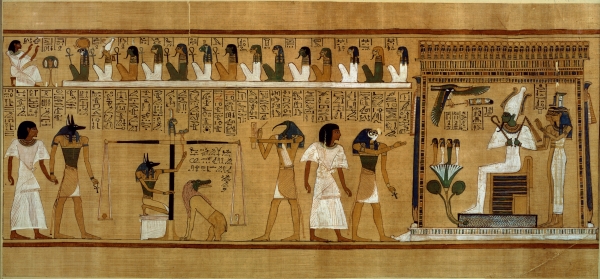

The heart, not the brain, is the record-keeper. It holds the memory of good and bad deeds; and of things left undone. Such was the belief of the ancient Egyptians. For that reason, one precept of their Book of Coming Forth by Day, with its Spells of the Dead, was that the heart (though an organ vital to life) was the key to the afterlife. The heart fell to be weighed in the scales against the feather of Maat. If the heart weighed more, then woe betide.

When Italian explorer, Giovanni Battista Belzoni discovered the sarcophagus of Seti I in 1817, the great King had been dead over 3,000 years. He ruled Egypt from 1294 to 1279 BC. Carved from a monolithic block of alabaster, Seti’s sarcophagus stood in the tomb’s largest hall, deepest of all that dynasty’s royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Fifteen years a pharaoh, how heavy the feather to weigh against his heart?

Inside and out, the sarcophagus bore inscriptions from the ancient Book of Gates, charting the journey of a soul through the Egyptian Underworld. The lid of the sarcophagus used to feature a sculpted portrait of the dead king. It was removed by tomb robbers. To borrow from Emily Dickinson, even the mighty ruler was not “safe in his alabaster chambers”.

Eight years later, in 1825, Sir John Soane caused a large hole to be knocked in the rear-wall of his house at 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields, London. This was to allow safe passage of the same sarcophagus into the underworld of his home. He had paid £2,000 for it. How much lighter then his wallet? Soane was resolved to make this tomb the very centrepiece of his collection in the ‘Sepulchral Chamber’, as he styled it. To celebrate the arrival, Sir John hosted not one but three parties, having succumbed to unchecked enthusiasm for showing off the last resting place of King Seti. An act of ostentation yes, but something more too. The design of the lighting, some of it within the sarcophagus, was supervised by Soane himself. Light forming shade, light contrasting the shades to create an atmosphere, it was said, thick with romance and melancholy.

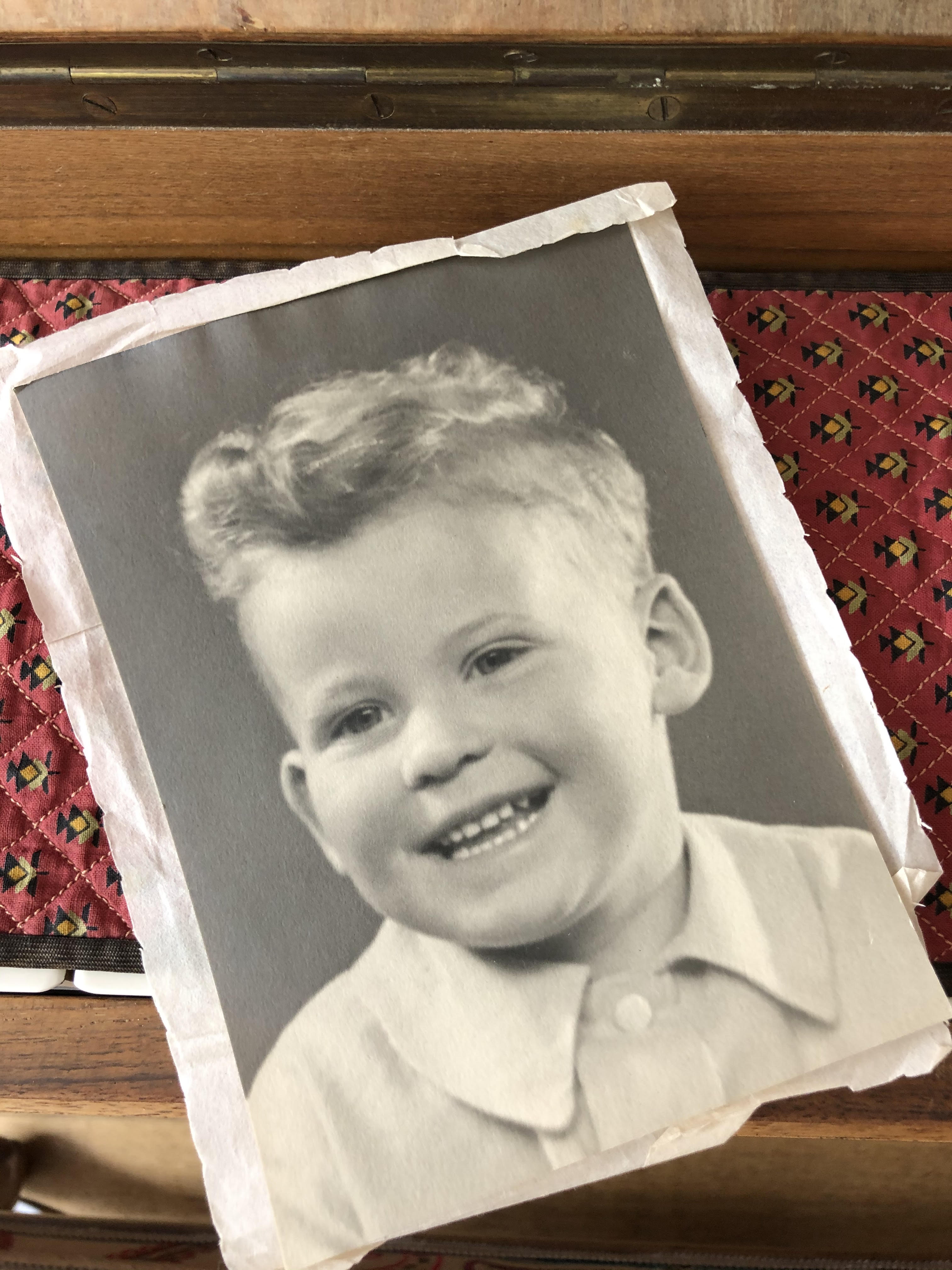

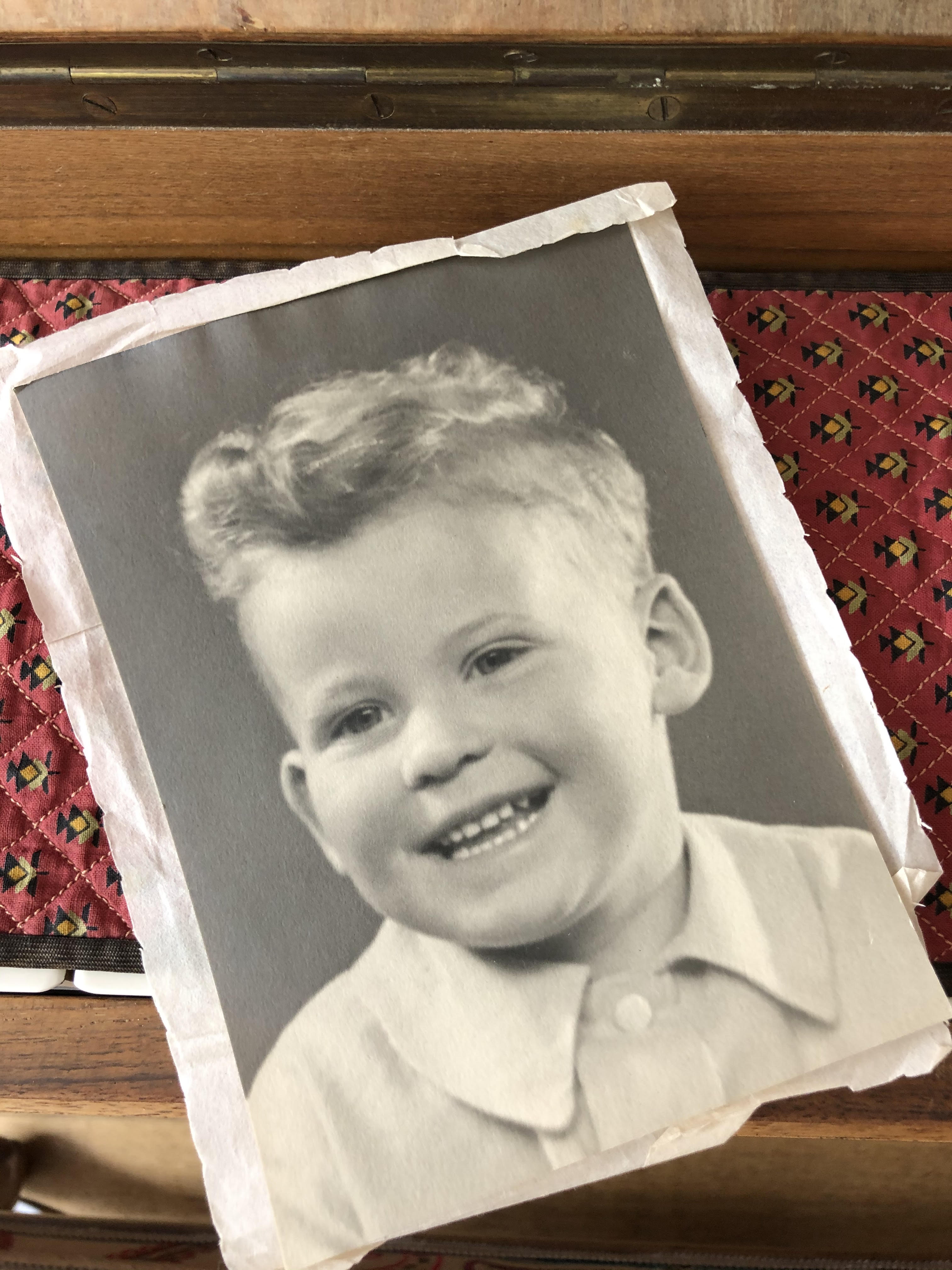

All of this would have delighted my father. He was alternately quixotic, morbid and exuberant. On high days, he succeeded in being all three at once. Visits to a “good ruin” (in truth, he never considered there could be such a thing as a bad ruin) would ritually be accompanied by gales of his gallows’ laughter, rising up from subterranean crypt or dungeon. Drawn to the lustre of funerary objects, in 1972 he stood long in the queue to gaze on Tutankhamun’s bright mask, then at the British Museum. So theatrical a name as ‘Sepulchral Chamber’ was a lure he could not ignore. He gazed too on the alabaster of King Seti’s sarcophagus, now darkening to a buff colour on account of London climate and pollution. Like Sir John Soane, it would not have occurred to him that other people might not be as elated as him by what they saw.

§

“I was dead you see”, my father began, in the telling of his dream to his sons. He described how, dressed in simplest plaid, he found himself on a bare, parquet floor in a grand house. On that floor were set three wooden objects: a piano, with its stool; and a coffin. Though he was laid out in the latter, he so wanted to sit at the former that he quit his coffin and went to the keyboard. There, in this reverie, he looked down to see his hands playing. What he witnessed were his fingers flying between octaves. He was performing Busoni’s transcription of Bach’s Chaconne in D Minor. This, for him, was the part that was all dream. Gifted though he was as a pianist, mastering the central sections of the piece had in life eluded him. Yet, there he was, using all but the last of his energies to be dazzling, note-perfect, playing the unplayable.

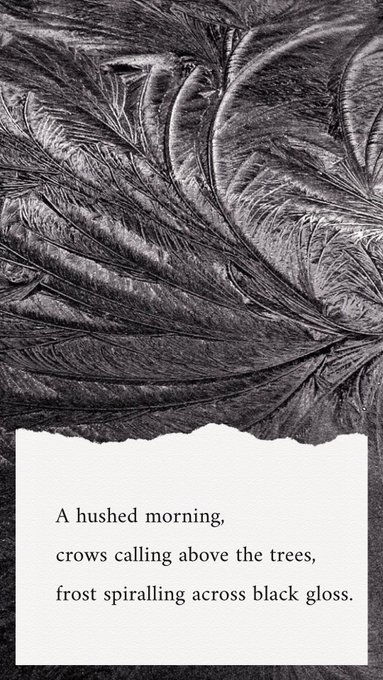

Just bars from the end of the piece, he could hear a noise in another part of the house. Until then, absorbed by the music, he had not considered whether others could hear this recital. “I was dead you see”, he said again. Not to cause distress to the keepers of that house, fearing they would find him slumped across the piano when they knew him already dead, he stopped playing. Back in the coffin, he laid himself out. Now, looking up, he saw one angel, and then another and a third. Staring harder, he noticed that this heavenly host was but a drawing on the inside of the lid to the coffin. Just as it closed shut upon him, he heard his last words to be: “Damn, I will never know”.

Whether there are angels, winged or not, in this life or the after-life, was a matter of some anguish to my father. Like the Victorian poet, Francis Thompson, he found himself chased by The Hound of Heaven. Those words “Damn, I will never know” spoke to that doubt. He found that living with hope was harder than coping with despair. He was, on balance, more unbeliever than not when it came to faith in the hereafter.

§

What were my father’s last words? Knowing him, with a baleful tone: “We’re going to be late”. Though “Old age should burn and rave at close of day”, that was not his death. He did not even make it to close of the day, let alone old age. In the afternoon of the 4th of July 1986, he just dropped down dead, aged 49 years. His dear heart, the record-keeper, had forgotten how to keep beating.

I am writing this 34 years later, to the day. It is the first time I have written, at any length, about him. The last time he wrote to me, at any length, was on my birthday. He wished me: “Success as the world counts it, the joy of friends, the dream of love and the consolation of equanimity”. No mention there of hope. The romantic, the disconsolate romantic present in “the dream of love” – not a wish for me to find love, at best, the “dream of love”. And then that last phrase: “the consolation of equanimity”. What a thing to wish an eighteen-year old.

In setting these words down, I find not so much grief, as an undiminished sense of feeling aggrieved. There was raw grief. It was some years before I could listen to his music without tears. Bach in particular set them flowing. But now, more a sense of grievance abides: at his loss and at my loss of him. Sharing his sense for the morbid, I worked out some years ago the day when son would have out-lived father: not a competition, just being marked by a marker in time. Now more years still have passed; more than half of my life without him; approaching three-quarters of his span in this world, since his death.

As well as Egyptology, my father loved etymology. Let me then, as an act of memoir, retrace the steps of these words back to their origins. Aggrieved comes from the old French, ‘agrever’, to make heavier – in turn, from the Latin of the same meaning ‘aggravare’ – all the way back to ‘gravis’ heavy. Set that against the family death notice, “… with a heavy heart, it grieves us…”. Grieves is from the old French, ‘grever’ to burden, encumber, and before then the Latin ‘gravare’, back once more to ‘gravis’. These words, cut from hard material, are now engraved.

That loss, the space left, becomes a burden, this is an etymological twist he would have enjoyed. Being a mathematician he knew how to turn a minus into a plus – and back again. As an actuary, he weighed Life Tables, more than the Spells of the Dead. But he would have seen that “feather” and “father” are close words, the latter just one vowel lighter. My grievance is not a cause for grievance. It is just another way of the heart keeping record that, having once been in the world, my father will always have been in the world. He was right to wish for the “consolation of equanimity”.

In memory of Anthony Patrick Limb

(5 October 1936 to 4 July 1986)

A P Limb was a son of Nottinghamshire, gifted not only with a facility for numbers and words but also music; he heard and saw the harmonies between all three. Possessed of a singular flair for blagging his way to performing on keyboard instruments at stately homes (harpsichords being a particular draw), he once even managed to persuade the keepers of the Great Organ at Chartres Cathedral to play a few bars.

P F Limb is his elder son and works as a barrister in the same county, where he serves on the Nottingham UNESCO City of Literature Board. He is the keeper of his father’s piano, a Pleyel upright and really likes words, especially ones with animus such as equanimity and magnanimity.

Birds of Firle is a single edition book by Tanya Shadrick being posted sequentially to 100 collaborators around the world, inviting responses to the idea of Grief and Hope as the things with feathers. Each recipient spends a few days with the book, before returning it with a hand-written letter and other small artefacts.